Review by Bill Long of Willamette University (Dec 12, 2004) and used with permission.

A Victorian Christmas Concert

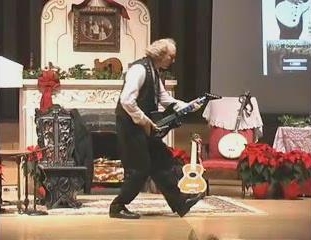

Earlier this evening musician John Doan kept a nearly-packed auditorium at Willamette University engaged for almost three hours as he introduced us to Victorian musical instruments and carols, and as he also provided a richly-textured, even “bardic” history of technological changes that influenced music from the 1840s to 1940s. Thus, Doan wore a lot of hats in his performance, but he changed them so skillfully, or “interweaved” them so seamlessly, that he gave us a coherent concert celebrating the joy of the season and underscoring the values of friendship, community and the creative power of individuals. His skillful presentation, careful scholarship, understated humor and professional demeanor give the impression that his star, already high in the horizon, is poised to rise still higher.

Earlier this evening musician John Doan kept a nearly-packed auditorium at Willamette University engaged for almost three hours as he introduced us to Victorian musical instruments and carols, and as he also provided a richly-textured, even “bardic” history of technological changes that influenced music from the 1840s to 1940s. Thus, Doan wore a lot of hats in his performance, but he changed them so skillfully, or “interweaved” them so seamlessly, that he gave us a coherent concert celebrating the joy of the season and underscoring the values of friendship, community and the creative power of individuals. His skillful presentation, careful scholarship, understated humor and professional demeanor give the impression that his star, already high in the horizon, is poised to rise still higher.

The Concert

One of the audience’s (and John’s) favorite instruments is the harp-guitar, which has almost the range of a piano, on which he played a twentieth-century “Ukranian Carol of the Bells,” the familiar carol “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” and a twentieth century arrangement of “Away in a Manger.” The mellifluous tones of the harp-guitar, complemented by the “audience as choir” in the first verse of the last two of these carols gave the evening a “call and response” character. Then, as he introduced us to other instruments or devices, from the Roller Gem Organ to the Parlor Guitar to the Mandolin, Harmonica, Banjo and Zithers, we felt as if we were receiving a tour through a finely-preserved Victorian mansion conducted by a skilled and genial guide.

He was not averse to bringing in very specific historical dates and individuals to vivify the presentation. For example, his introduction of John Philip Sousa’s 1906 essay, “On the Menace of Mechanical Music,” warning against the danger of the phonograph as opposed to the pure musical rendition by an artist, brought alive an issue that few of us had ever contemplated. What he didn’t mention, however, and this could aid his presentation, is that Sousa’s essay was driven primarily by economic motives–Sousa’s marches had been wantonly and profitably appropriated by makers of records and music rolls, and Sousa rightly wanted to recover payment for all the sheet music royalties he was losing. More particularly, Sousa was responding to a recent federal appellate court decision siding with the makers of the music rolls over creative artists like Sousa.

Again, he referred to an essay “The Robot’s Lullaby,” issued by the American Federation of Musicians in the early days of the Great Depression (1930), excoriating the new practice of producing films with a musical script, the effect of which would be to put thousands upon thousands of musicians (who played piano/organ for silent movies) out of work. One gets the impression that the protest was about as successful as those objecting to the use of robotics in American automobile manufacturing in the late 1970s, but it still added a sharp historical point to his presentation.

The Singer as Bard

But more than a skillful historical lecturer interspersing instrumental pieces and audience sing-alongs, Doan was playing for higher stakes. In fact, he wants to be a story-teller, a bard of sorts, one who will tell us about ourselves as he tells us our musical past. He wants us to see ourselves in the crowd around the Victorian piano of the 1880s or those gathering around the new invention of the radio in the 1920s. He wants us not only to listen to the music he presented but to make our own entertainment by becoming part of the story of the music he brought to us. He has a great respect for people who have stories of the past that relate to musical instruments (and he told two or three deeply-affecting stories of instruments), and he would like us all to realize the wealth that there is among us and the older ones of us in reaching back to another time and describing life as it was once lived. What is at stake for Doan as bard, however, is more even than what Woody Guthrie or other American folk artists have done in connecting us to our American musical past. He would like to take us back to the celebrations of our deep past, our religious heritage, our ancient European roots, and to find ourselves in forms that were once so vital and can still be vital today.

John Doan Victorian Christmas Maestro CBN Interview

Conclusion

John does not have the “big personality” or richly resonant voice of a man to whom he dedicated his encore number “Farewell,” Burl Ives. Thus, I do not imagine that he will ever sing “The Big Rock Candy Mountain” or “Have a Holly Jolly Christmas” to the delighted squeals of young and old alike. Yet, his quiet persuasiveness and subtle humor has and will enter into our hearts. As a historian and legal scholar/rhetorician, I see how he can grow yet further in his ability to tell a historical story. But he has all the tools to do it.

As I was scanning the audience near the end of the concert I discerned that they not only appreciated John but loved him too. It is a rare performer who can generate affection, but John can do it.