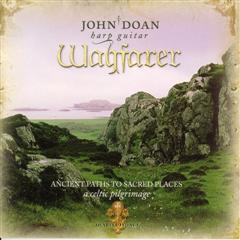

Wayfarer

by John Doan

CD Price $15.97

John Doan brings back soulful and provocative musical sketches from a pilgrimage to the most sacred sites of the Celtic Isles. The twenty-string harp guitar is featured throughout in his most virtuosic outing joined by exotic percussion, ancient instruments, a choir of monks, fiddles, tin whistle, cello and more. Follow the ancient pilgrim’s paths to locations made famous by the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland”, along roads to secluded sanctuaries, and by boat to remote island retreats. Adventurous, thoughtful, and renewing – a journey memorable for its achingly beautiful moments and encouraging spirit. This CD includes a twenty-page booklet giving an in depth look into the inspiration behind each composition.

Listen

- Skellig Michael – A Rock in the Sea 4:14

- Wayfarer – On the Path to Holycross Abbey 4:37

- Gazing On the Face of the Sea 4:01

- Festival 3:34

- The Way of My Fathers 5:11

- A Pilgrim’s Hymn 4:10

- St. Brendan – Recounting the Voyage 4:16

- Run to Sanctuary 5:00

- Castle Dinas Bran – Procession of the Holy Grail 4:20

- St. Joseph Arrives in Avalon 4:47

- The Hunter and the Hare 5:21

Wayfarer – Reviews

John Doan’s music has restorative properties. Listening is like embarking on an inner pilgrimage. Wayfarer is a musical pilgrimage reflecting an actual journey to sacred sites in the British Isles. The first notes seem like an invitation to come on the journey. “Where indeed are we going? And why?” Listening to this music, we can go within to remember an ancient place where the temporal seems to touch the eternal. Locations known as “thin places” to Celtic Christians gave them this sense. We can step back in time, slow our hectic pace, and reflect upon the joys of simplicity. More than a CD, this is history lesson and guided meditation in one, thanks to the extensive liner notes. Each piece of music receives a page in the liner notes with a quote suitable for meditation, and an explanation of the holy site that inspired its composition. Although one can listen without reading the booklet and enjoy the music, it becomes more meaningful to read along. It definitely deserves a higher place than just background music.

The high quality of this CD is evident in its varied and interesting arrangements and masterful, sensitive, expressive playing by all the instrumentalists. The unique sound of the 20-string harp guitar is at once powerful and intimate, evoking an atmosphere of mystery and wonder. Precise, virtuosic playing and impeccable timing with musical flexibility is always apparent. Such amazing tone, in both low, rich, resonant ranges, and on high, clear, crystalline notes. A Medieval mood sometimes prevails, as in “Festival,” with the presentation of crumhorns and doodlezock. Most tracks inspire reflection but this one with its good humor, percussive energy and a deep guttural quality to the sound of the harp guitar makes one want to snap one’s fingers and dance. Amongst various ancient instruments, a Portuguese viola also makes an appearance.

A significant sense of artistry in the cover photos and inside drawings (by Deirdra Doan) completes the unified theme.

“Our noisy modern times whisk us along without allowing space for the silence we need to hear our creative imagination and the voice of God speaking to us” (liner notes p. 9). Thanks to John Doan, we have a visionary musical gift that can let us time travel to a “thin place” and find rest for our souls.

Heather Beckmyer – Celtic Christian Tunes (APR 2, 2006)

When you hear Doan play, it sounds like more than one musician performing. Wayfarer is… a collection of songs woven together with the intricacy of a Celtic knot. Doan’s gorgeous melodies lift off the heather … and go beyond the Celtic cliches and rote standards for an album that brings the mystery back to Ireland.

john diliberto – echoes (national public radio program) (may 25, 2006)

“Fascinating history … Enchanting melodies … backed by lively percussion and Celtic guitar. Wayfarer is recommended for fans of Celtic-inspired music looking to broaden their understanding of this unique culture. Doan documents his journey in great detail, adding a tremendous educational aspect to his spiritual music.”

CDNOW (May 25, 2006)

“Inspired by ancient Celtic legends and holy places, John Doan and a group of other excellent musicians provide us with polished instrumentals. The 20-string harp guitar provides an ‘old’ feel to these new tunes and a haunting, ‘Celtic’ quality. His flair with the harp guitar carries each tune well and keeps the listeners’ interest.”

U.S. Scots Reviews (May 25, 2006)

“Doan’s original compositions musically recreate a series of pilgrimages to sacred sites. The beautifully researched and illustrated liner notes include fascinating stories to accompany each musical selection. Doan’s instrument of choice is a harp-guitar, an elegant and complex instrument, ideally suited to his unique brand of musical storytelling. Subtle layers of supporting instrumentation embellish each of … Doan’s carefully wrought musical conceptions … with respectful delicacy. Surely all pilgrims and others attracted to the “thin places” (those spots where the veil between time and place begins to dissolve) will find assurance in this music.”

New Age Voice (May 25, 2006)

“Since discovering John Doan, I have been fascinated by the sound he creates. The harp guitar … possesses the haunting qualities of the harp and is perfectly suited to an Irish setting. Doan composed the tunes which went gracefully form early to traditional in feel. There is a distinct connection with old melodies, yet Doan possesses a timeless quality in his playing – the music is both old and new.”

Putting On Airs – Irish Edition (May 25, 2006)

“From the side of the wood stove in Alaska ..and I don’t even like Celtic-inspired music. John Doan is a real treat. If you have never heard any of his solo releases (this one and Eire), have a listen to some of the samples here. This Oregon-based musician primarily plays guitar (and other instruments as well) on this CD. His talent is truly amazing. He brings effortless-sounding technique to the music making it complex and accomplished, yet not over-powering. There is a Celtic feel to the music, but this is not the traditional jigs and reels music. This CD is more contemplative, and evokes a mood of green lands and misted hills–after all, it is on the Hearts O’ Space label. There is some addition of complementary sounds in the music, such as distant church bells, but the additional stuff doesn’t make the music sappy or contrived. Each piece is a treat on its own, so listen to any of the samples, and you will get an idea of the spirit of the music. Doan also has a wonderful Christmas CD available from Hearts of Space–try it, too.”

Aurora Lyn – Music Review (May 25 2006)

Wayfarer – Ancient Paths to Sacred Places (Liner Notes)

“Our modern world seems to have lost that fascination and compulsion which once drew so many into pilgrimage… The whole concept of pilgrimage now appears anachronistic, irrelevant to the host of other demands that we face… And yet, when we are stilled for a moment, when we allow ourselves a respite from television’s bland sound-bites and our computer’s flickering pixels, the question arises: where indeed are we going? And why?” Michael Baigent (co-author of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail)

“Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls.”

Jeremiah 6:16

Ever since I was little I have been puzzled by the passage of time and have come to appreciate that it exists, if for nothing else, so that everything does not happen at once. The awareness of time passing has come to the forefront these days as

we set down the path of Y2K, anticipating its joys yet all too aware of growing tensions in the world around us. As we stand now at the crossroads that extend from out of the past, the question arises: “where indeed are we going? And why?”

I set out to revisit sites that served as a light in a dark age leading up to Y1K that had been the destination of countless yet forgotten pilgrims asking just those very questions. I caught a glimpse of another time when the human experience was shaped by the glory of landscapes, the activity of animals, sunrises and sunsets over sacred “thin” places, and where an atmosphere of miracles and prayer prevailed.

I was moved to visit the sites made famous by the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland” that included St. Columba and St. Brendan; to rediscover centers of sanctuary and secluded island retreats; and to uncover some of the mystery in the ancient spiritual tradition of the British Isles claiming to be the site of the world’s first above ground church for the followers of ‘the way’ as well as the possessor of one of its most profound relics – the Holy Grail. This journey seemed a radical contrast with our modern times where we tend to identify with media, not the world, while favoring material pursuits over taking time to develop the symbolic and spiritual side to our nature.

Looking for the good roads to travel, map in hand and an adventurous spirit at heart, I felt renewed, appreciating how life itself is a sacred journey through time, a precious gift to be cherished. As you listen to the music I developed from sketches recorded at each site, I invite you to become a wayfarer upon ancient paths to sacred places. Perhaps it will be a moment of rest for your souls as it has for mine.

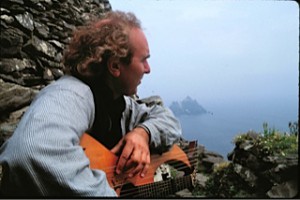

Skellig Michael – A Rock in the Sea

“As I climbed the path winding up to the ancient construction near the top of that cliff, I sensed that I was on the threshold of something utterly unique. Nothing in my experience had prepared me for the huddle of domes, crouching halfway to heaven in this all but inaccessible place, with an intimidating immensity of space all around, where it was easy to feel that you had reached a limit of this world.”

Geoffrey Moorhouse (author of Sun Dancing – A Vision of Medieval Ireland)

My visit to Skellig Michael, a small island ten miles off the point of the Iveragh Peninsula, was one of my most exciting adventures to a sacred place. This lonely site well suited for solitude and prayer served as a remote monastery that was not only the westernmost outpost of Christianity in the old world but was revered as one of the most holy spots in all of Ireland. It appears as a defiant arm of granite reaching some seven hundred and twenty feet up into the grey cloud sky. It is almost impossible to reach safely most times of the year given to the tremendous ocean swells and crashing surf.

St. Finian is said to have founded the tiny monastery in the 6th century where it remained a safe haven for worship until the Vikings began their attacks three hundred years later. It is dedicated to the Archangel Michael, who not only presided over high places but is said to have helped Saint Patrick chase the snakes out of Ireland. Inspired by the desert fathers to seek God’s voice out and away from the cities, these courageous monks found here the constant reminder of God’s awesome force as they braved the elements of rain, wind, and cold within beehive shaped huts of piled stone.

One of their primary duties was to pray for those who have not heard the word and or have not believed it while also hoping to do spiritual battle against the spirit of plague, pestilence, and warring powers.

I hired a boatman to take me out to that rock in the sea. Upon arrival he positioned his boat so I could jump ashore when the twelve foot swell raised us up to the dock. There were 600 steps chiseled into the rocks by monks ages ago. They were worn smooth by millennia of storms and footsteps that had lead faithfully to the compound high up near the top peak. Along the ascent the brisk air was busied with Gannets, and Puffins and other strange fowl. Once at the top it was like stepping into another time as I walked among the stone huts and felt an intoxication looking out upon the sweeping panorama of clear blue water, unworldly cloud formations, and powerful focused shafts of light. I tried to capture with this music a sense of this drama, this adventure in living that I found at Skellig Michael – a rock in the sea.

I hired a boatman to take me out to that rock in the sea. Upon arrival he positioned his boat so I could jump ashore when the twelve foot swell raised us up to the dock. There were 600 steps chiseled into the rocks by monks ages ago. They were worn smooth by millennia of storms and footsteps that had lead faithfully to the compound high up near the top peak. Along the ascent the brisk air was busied with Gannets, and Puffins and other strange fowl. Once at the top it was like stepping into another time as I walked among the stone huts and felt an intoxication looking out upon the sweeping panorama of clear blue water, unworldly cloud formations, and powerful focused shafts of light. I tried to capture with this music a sense of this drama, this adventure in living that I found at Skellig Michael – a rock in the sea.

The Way of My Fathers

“In the Holy Scriptures this day is called the Sabbath, which is to be interpreted as the day of rest. A true Sabbath is it for me, for it is the last day of my present laborious life, and upon it I rest from my labors: and this night, at midnight, when begins the solemn day of the Lord, according to the Scripture, I shall go the way of my fathers.” St. Columba, Iona, Scotland, June 8, 597 A.D.

This was a “secret” Columba confides in his fellow brother the day before his passing. Diormit refuses to believe it. Soon after a white horse, used to carry milk-pails from the byre to the monastery, comes to the saint whinnying plaintively and shedding tears. Diormit tries to drive it away but Columba instructs him “Let our friend alone, let him pour out his bitter grief into my bosom. Behold thou, as thou art a man and hast a rational soul, canst know nothing of my departure beyond what I myself have just told thee; but to this brute beast, devoid of reason, the Creator Himself has in some way manifestly made it known that its master is about to leave it.” After resting for a while, Columba climbs a little hill overlooking the monastery and says his goodbyes to this world. He returns to his cell and transcribes from the thirty-fourth psalm “They that seek the Lord shall not want any good thing.” As evening approached he lay on his stone bed to later be awakened by the ringing of the bell for midnight service. He rises in haste and runs to the church in great excitement where on bent knees falls down in prayer beside the altar. Diormit followed and saw at the same moment as the saints passing that the whole church is filled within with angelic light.

Centuries later, on the fourteen hundredth anniversary of Columba’s death, I entered into the darkened cathedral just as the midnight bell rang lonely over the hush of the surf and whisper of the sea breeze rushing past the outer stone walls. I did not plan to be here at such a symbolic moment. It was the only time the sanctuary was at rest from the business of ceremony. It was as if a comforting fog of sleep flowed in from off shore in a tide of dreams. I ventured toward the flickering light of candles resting before the altar. In all the mystery and drama of this cavernous “thin” place, there was a distant echo of chanting and imaginary bells clanging. I could see dimly the saint’s last hours, where a lifetime passed before him giving way to eternity and to his desired rest in the presence of his maker. His faith and courage gave way to a moment of doubt and then surrender.

As I sat there and played for hours, I realized that something of Columba was still present. Perhaps I was feeling a sense of his temporal humanity contrasted with his enduring faith that encourages us to invite the miraculous into our lives.

Wayfarer – On the Path to Holy Cross Abbey

“In today’s world it is difficult to imagine the power that relics, shrines and sacred images exerted over the medieval mind… their wider social, political and religious significance should never be forgotten.” Raghnall O’Floinn (Assistant Keeper of Irish Antiquities, National Museum of Ireland)

I arrived at Holycross Abbey late in the afternoon just as the church bells announced the coming of night. I had travelled along the old pilgrim’s way that followed the Suir river five miles south of Thurles, Co. Tipperary, Ireland. I hiked into the most ancient ruins of the compound finding myself surrounded with high walls of chiseled grey stone with a roof that reached up into a canopy of sunset lite clouds overhead.

My harp guitar wove its reverberant bell like tones with the songs of birds nesting where mortar has given way to bits and pieces of grass and twigs. I could feel the spirit of adventure of those pilgrims of old who weathered great hardships to catch a glimpse of an ancient mystery.

This place remains an important place of pilgrimage as it still treasures a piece of dark wood from the True Cross said to have been stained by the blood of Christ and brought back from the holy lands. Once at the Abbey it was carried in a bag hung about the abbots neck when he went on circuit to enforce ecclesiastical laws, collect taxes, preside over sworn oaths and treaties, to be present at the battlefield to ensure victory, or to counter the forces of evil in times of plaques, bad weather or natural disasters. The possession of relics by a church or monastery served to increase its status and wealth and ensured special protection to the community, not to mention attracting pilgrims – a valuable source of income.

This wood, like many other relics, was seen as a window to another world, touched as it were, by someone who has seen into the other side. Relics became like footpaths worn into the forest, like canyons cut by a river that has made its way to the sea, a passage way to the beyond. To behold a relic then was to experience a tangible artifact of faith, a material thing to focus ones attention on, making believing in the mystery of God and the creation all the more real.

The pathways to these various sites where relics were stored became known as the Pilgrim’s Way and the Pilgrim became known as a Wayfarer. It also suggested that they were follower of ‘The Way’. Whether wealthy or poor, Famous or unknown, you traveled the Way as an equal just as we came and will leave this world. To become a pilgrim ones personal drama in life was left behind as your family, friends, and neighbors walked with you to the boundary of the village and blessed you on your way. Each step, each turn was a riddle to take joy in solving as the mind became free, and thoughts became simple until upon arrival all that was left was you standing before the relic window to the great I Am.

St. Brendan-Recounting the Voyage

“After their explorations they met a young man who said: ‘this is the land you have sought after for so long a time; but you could not hitherto find it, because Christ the Lord wished first to display to you His divers mysteries in this immense ocean. Return now to the land of your birth… and after many years it will be made manifest to those who come after you.’ After leaving the island, Brendan set sail in a direct course, under God’s guidance, and arrived at his own monastery.”

Navigatio Sancti Brendani 10th century AD.

In the Age of Saints the known world reached out into the Atlantic Ocean only as far as the Dingle Peninsula of Ireland. It was here, around 500 AD, a great seafarer and saint by the name of Brendan hiked to the top of Ireland’s second highest mountain. After much fasting and prayer, he had a vision: “of a beautiful noble island … where the angel of the Lord spoke thus: ‘I will … teach you how to find the beautiful island of which you have had a vision, and which you desire to attain.'” Although, off in the distance he could see the rocks of Skellig Michael where brave monks lived an austere life, the island of paradise he envisioned laid well beyond. He and his fourteen followers soon after built a simple coracle and set out into the sea serendering to wherever the winds would take them. This ardent pilgrim’s quest led him to discover many far off Islands, icebergs, and even North America some eight centuries before Christopher Columbus.

Fifteen centuries later I visited Brandon Mountain and could feel a sense of great mystery as the wind torn clouds occasionally revealed the vast expanse of open sea inviting one’s imagination to wonder what lay beyond. I then followed the pilgrim’s track down the Saint’s Road that joined Brendan’s Creek. It emptied into a narrow protected bay where vision became action and the voyage began. After attaining his discovery of the Isle of Paradise, Brendan’s legacy finally touched ground where he founded the famous monastery at Clonfert, Co. Galway. It is here, far from the mountainous shores of Kerry, where he lived into his ninties recounting mysterious tales of legendary journeys to the innocent who could only dream of such adventures.

Late in the afternoon I entered into the old Cathedral on the site, finding it quiet and devoid of any souls. I explored back into the dark recesses of the church and found down a narrow hallway a dimly lit cavelike room that appeared to be of great age. I sat and mused over the tales that Brendan and his followers might have told by candlelight in this reverberate room. I tried to capture one of those sessions that recounted the voyage of sailor monks who discovered one fantastic island after another overcoming peril by spiritual fortitude and unswerving faith.

Gazing On The Face of the Sea

“Delightful it is to stand on the peak of a rock, in the bosom of the isle, gazing on the face of the sea. I hear the heaving waves chanting a tune to God in heaven; I see their glittering surf. I see the golden beaches, their sands sparkling; I hear the joyous shrieks of the swooping gulls. I hear the waves breaking, crashing on rocks, like thunder in heaven. I see the mighty whales. I watch the ebb and flow of the ocean tide; it holds my secret, my mournful flight from Eire.

St. Columba, Iona, Scotland 563-597

As the ferry slowly floated into the landing at the Isle of Iona, I was filled with wonder about this “thin” place where for centuries pilgrims gathered to be within the thin divide between past and present and heaven and earth. If one was to measure time in relation to eternity, the 1400 years have passed in but a moment since St. Columba himself walked the golden sandy beaches that cushion the island from the immensity of the swelling tides. He is revered as Scotland’s most famous Saint, and is spoke of in Ireland in the same breath with St. Patrick and St. Briget.

As I stood at a peak of rock and gazed out to sea I felt as if I was being embraced by the fragilness of the moment where the past and future came together holding me so gently in its arms. A sacred sense of being alive was invigorated by breathing in the cool salt air as it kissed my face and stoked my hair. I was startled to hear the heavy waves thunder in the surf, but was comforted by their regularity unending, their power certain. My imagination stretched out across the vast expanse of sea and sky and back in time to St. Columba.

Born a prince in a powerful tribe in the Northwest of Ireland in 521 AD he was destined to rule over men on this earth. As a bishop he established many monasteries throughout his homeland pointing his followers hearts to the world beyond. It was a fine line straddling both worlds as it were, Columba the saint, Columba the statesman. After forcing an issue with the High King who had broken the right of sanctuary to punish one of his followers, a great battle ensued at Cul Dreimne, a little north of Sligo just beneath Benbulban, where three thousand of the king’s men were laid dead. For this Columba was exiled by his peers never to return home. The pain of this loss was given some small solace by settling on the isle of Iona just far enough away that Ireland could not be seen from its shore. He begins another community that eventually was responsible for setting up missions through Scotland, England, and the continent bringing the love of learning, the gospel, and civilization back to a people who had been lost to a dark age.

This music welled up from my imagination in the moment I glimpsed Columba the man grieve the loss of his earthly home, its people and past joys who had drifted just beneath the horizon in his life, contrasted with a resolve of great faith in a God whose presence is so richly expressed through his creation yet whose house resides just beyond this world.

Festival

“We will go with our young and old, with our sons and daughters, and with our flocks and herds, because we are to celebrate a festival to the LORD.” Moses Ex.10:9

Throughout the British Isles during the golden age of Celtic saints there was much time given to celebration just as had been chronicled in the ancient writings of the Hebrews millennia before. What had been popular events centered around the worship of various gods and nature spirits became reinterpreted to come in line with the new vision of missionaries and their followers of “The Way.”

In the year 597 A.D. Pope Gregory sent Augustine to south-east England and among his orders was to systematically destroy pagan altars and images. He was careful to point out that “the idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed with holy water … and purified from the worship of demons and dedicated to the service of the true God.” He allowed for the sacrificing of oxen to the praise of God so as to continue the tradition of old feast days. “If the people are allowed some worldly pleasures in this way, they will more readily come to desire the joys of the spirit.”

A whole variety of feast days followed intended to be the joyful celebrations of Christian Mysteries such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost (Whit Sunday) and the devotion in particular places to patronal saints. Holy days then were early versions of our holidays now. People took great joy in ceremony and tradition busying themselves decorating the church, bringing out the finest furnishing for the altar and the best vestments for the service. Within each home the festive mood was expressed by draping chairs, displaying table decorations, renewing floor coverings, etc. Lit candles and incense as well as more elaborate music and much ringing of bells were everywhere to delight the senses. The culminating event involved assembling in a large group or at a public festival where everyone ate sumptuously on generous provisions prepared just for the occasion. People created their own entertainment, rich and varied, where all had a part in the festivities.

There were several sacred sites that I visited where the spirit of celebration was a delight and feast for the soul. As John O’Donohue, Ireland’s best selling poet comments, “real celebration is the opposite of contemporary consumerism. In fact, consumerism gradually kills both the desire and the capacity to celebrate… enough is never, ever enough.” It is my hope that remembering traditions with symbol and celebration can restore joy to our hearts and lift our souls to sing and dance again. This is what I tried to capture in imagining an immortal moment in life’s festival.

St. Joseph Arrives at Avalon

“Why Joseph of Arimathea has been indifferently by-passed, along with historic events covering that epochal period is both perplexing and surprising… as he was the true first Apostle of Britain five hundred and sixty-two years before St. Augustine. He, with twelve other disciples of Christ, erected in England the first Christian church above ground paving the path for the proclamation of ‘The Way’ to the world.” George Jowett (author of The Drama of the Lost Disciples)

Centuries ago Avalon had been one of the most sacred sites in all of the British Isles. Situated now in the quiet little town of Gastonbury, it was then an island, twelve miles inland, up a protected inlet carved into southwestern England. During the Saxon period monks drained the land to form a dry plain transforming islands to hills. It is here where legend tells us that a wealthy man named Joseph, along with twelve of his disciples, arrived in 36 A.D. cutting through the glassy waters in his wooden ship under cover of a starlit night. For weeks they had braved the Mediterranean Sea, then out into the Atlantic beyond the control of Rome, and finally around the southern tip of Cornwall. Weary were all from the long voyage, hence the island they first touched ground upon became known as ‘Weary All Hill’.

Joseph had been to the mines in Cornwall many times before filling his ships with copper and tin to trade with his people back in Israel. But this time his sole cargo was a cup – a Holy Grail considered of more value that all the cargoes that had ever sailed upon the seas. It was believed to be the cup that Jesus and all his disciples drank from at the last supper, and the sad cup to catch the blood of Christ upon the cross. Joseph, thought by some scholars to be the uncle of Jesus was also the disciple that gave up his own tomb for Christ’s body. After experiencing first hand the dramatic events of Christ’s Passion St. Joseph, the Apostle to Britain on orders from St. Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, made this an historic landfall as it was to be the beginning of a new mission to form the world’s first above ground church for the followers of “the way” not yet known as Christianity. Centuries latter, Queen Elizabeth herself cited this lineage when declaring the British Kingdom as the true “Defender of the Faith” not Rome, thus pushing the western world further into the Reformation.

To make this sketch I sat in a field on the hillside of Glastonbury Tor imagining the scene of two millennia ago. While huddling beneath my umbrella to shield me from the sporadic mist and rain, it was quite dramatic to see a veil of clouds float past to reveal a ground fog part way up Weary All Hill making Avalon appear once again as the mystery isle of old.

Castle Dinas Bran – The Procession of the Holy Grail

“This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you.” Jesus Christ Lk 22:20

In Wales, high above the river Dee and the valley of Llangollen, are the hilltop ruins of the ancient fortress of Dinas Bran, the most likely site of the Grail castle as spoken of in the Arthurian legends. In medieval literature it was known as Corbenic, a derivation of the name raven or crow many of which still haunt the sky above the castle walls. It is often associated with Bron, the Fisher King, son-in-law of Joseph of Arimathea and grandfather of Perceval. One version of the story begins with Joseph obtaining the cup used by Christ at the Last Supper. He catches within it some of Christ’s blood while caring for the body at the tomb. His sister and her husband Bron, sail with him to Britain, where he sets up the world’s first Christian church at Glastonbury.

Here the Grail is housed, and serves as a chalice at the celebration of the Mass. The Grail eventually is passed on to Bron who becomes known as the Fisher King as he is said to have fed his followers with a single fish from the Grail, emulating Christ’s feeding of the five thousand with five loaves and two fishes.

Having a wound that never heals he is suspended in a state between life and death while the land around his castle becomes a waste land. Centuries later, The Grail appears to King Arthur and his knights as they were gathered at the Round Table. They beheld it in holy awe until it vanished causing Merlin, head priest of Arthur’s court, to urge the knights to make a quest to find it. Obtaining the Holy Grail would bring union with the divine as well as healing to the Fisher King and life back into the barren land. The legacy of the Grail was the dominant motif for European literature in the middle ages and came at a time of great outpouring of mystical writing. It seems that a sense of loss pervades the legends, a separateness from the divine that is thought to be only renewed with contact with the holy relic of the Grail.

The origins of this might be found in the fourth century when a critical shift in perspective happened moving from the experience of holiness from within oneself to thinking in terms of objects being holy things controlled by mediators of the faith. As Emperor Constantine in 313 A.D. issued an edict for peoples of the Roman Empire to welcome a new religion of Christian faith the door was open to create a spiritual parody of the Roman Empire with its centralized control and world view which ultimately would clash with the original mission of St. Joseph the Celtic expression of the faith he found there.

As I sat perched out an open window of the empty ruins I imagined the arrival of the Grail to Dinas Bran. There was a grand procession of monks and pilgrims walking past single file each holding a small candle, creating a string of flickering lights reminding them that they would never walk in darkness but would have the light of life within them.

A Pilgrim’s Hymn

“Each Ancestor, while traveling through the country, was thought to have scattered a trail of words and musical notes along the line of his footprints… A song was both map and direction finder. Providing you knew the song, you could always find your way across country … I felt the Songlines were not necessarily an Australian phenomenon, but universal … ” Bruce Chatwin

“The early Celts believed in “thin places”; geographical locations scattered throughout Ireland and the British Isles where a person experiences only a very thin divide between past, present, and future times; places where a person is somehow able, possibly only for a moment, to encounter a more ancient reality within present time; or places where perhaps only in a glance we are somehow transported into the future.” Edward Sellner (from Wisdom of the Celtic Saints)

I personally don’t think that one has to go to sacred sites in the British Isles to experience the excitement and discovery of a journey. That was what I choose to do as an adventure in my life. Just leaving the confines of our mechanical times behind and exploring nature anywhere could be renewing. It is an opportunity to contrast our life experience against a backdrop of the greater and real world around us versus the imagined comfort we might feel living within surroundings of our own design.

Although we must spout, bloom and thrive where we are planted, we must also nourish our souls to remain vital and strong. Just taking a moment to enjoy the call and flight of birds in the trees where we live, or to wonder at the play of shapes of clouds overhead can be calming and restoring. Our modern times tend to be filled with noise and sounds of all kinds of media whisking us off into a world of make believe and passing issues without allowing spaces for silence. Not that we shouldn’t enjoy fantasy from time to time but if we are to commune with our deepest thoughts or to give rein to our creative imagination or on occasion to hear the voice of God speaking to us we must give time to silence.

As I went from one sacred site to another I heard within myself a faint tune which at first seemed to echo the peaceful rolling lay of the land, the soft wooly sheep in the fields, and the delight of discovering a shimmer of purple heather along side the road. What first seemed a vague mood became an emotion of comfort and solace finally to blossom forth into the form of a hymn. Perhaps some quality of spirit of those bare footed seekers upon these well traveled paths had lain dormant for centuries waiting to be felt again by any who trouble to follow in their footsteps.

Maybe it is simply being in the act of experiencing the world anew that we rekindle the essence of pilgrimage. Our first years of being are what we are given, our later years seem to be more what we have chosen. Many pilgrims of old, especially the Celts, chose to surrender their own folly and wisdom to delight in hearing God speak through the warmth of the sun upon their face, the respite of a shade tree, the authority of thunderous clouds, while pondering it all in relation to the inspired words spoke to man and handed down through the ages. The mystery of a personal relationship to God outside ourselves, that was in a pilgrim’s heart, and in song, a pilgrim’s hymn.

Run to Sanctuary

“You are my hiding place; you will protect me from trouble and surround me with songs of deliverance.” King David Ps.32:7

Toward the end of a day journeying in a remote part of Wales I thought to seek shelter at an old farmhouse that had a room to let. After a warm welcome from my hosts I began to explore the pastoral setting surrounding the place. It was tucked securely into a small valley that had been cut by a winding stream that was now subdued by a season of dry summer days. The sheep wandered openly as they crossed the gravel road on their way to feed within a fenced area where they would take refuge from the prowlers of night.

Behind the house was a hill so tall it could almost be called a mountain (and in fact was the backdrop for the recent movie “An Englishman Walked Up a Hill and Came Down A Mountain.”) Unseen, on the other side, is the church of Pennant Melangell that not only served as a center of pilgrimage but also as a sanctuary for fugitives, defeated soldiers, and people on the run. This safety was called “right of sanctuary” and was honored nearly a thousand years ago when these valleys were within the kingdom of Powys. The tradition went back to ancient Palestine where there were six cities set apart for those who killed another person either accidentally or in self defense. There they were assured to receive a fair trial.

The sacred place within the temple at Jerusalem was called the Holy of Holies. It was a sanctuary in which was kept the ark of the covenant, and into which no person was permitted to enter except the high priest and that only once a year to intercede for the people. Eventually, the sanctuary became the part of the church where the altar is placed as well as a place of asylum. As I sat and played into the twilight, I imagined those fugitives running to safe haven up and over this hill hoping to have a respite from pursuit. “I am almost there,” they might have said to themselves as they pause to regain their breath. But the hounds are still on the trail. I tried to capture that sense of longing for a hiding place we all hope for in times of need where we are protected from trouble and surrounded by songs of deliverance. Trusting in the unseen over the hill to a place you know is safe is the stuff that faith is made of, a run to sanctuary.

The Hunter and The Hare

“Even when human life is apparently most fulfilled and successful, we can become aware that there are dimensions of existence which altogether escape us, dimensions of life where we are in fact powerless, where we too like the defeated hare can only cry “Melangell hide me.” A. M. Allchin

“The hare declares, ‘All I have been, am, she shelters.’

‘Not I, ‘the saint says, ‘It is my Lord.’ Ruth Bidgood

I had heard tales of the peace and shelter of Pennant Melangell, a little sanctuary, hidden in the hills of Wales, just 35 miles across the border from Shrewsbury, England, so I aimed my steps upon an ancient path that had been travelled by pilgrims for over a thousand years. A winding road lined with thick tall hedges lead through a narrow and solitary valley to a clearing where stands the old church that bares St. Melangell’s name. Within it is one of the only shrines to a saint that withstood destruction from an outside world during the reformation.

As I looked about the heavy wooded slopes there was a distinct and peaceful quiet that was occasionally broken by the singing of birds and the rustling of wild rabbits among the bushes.

Melangell was an Irish maiden promised by her father King Jowchel to marry a tribal prince. Rather than marry she choose the life of a nun and left Ireland for Wales. After journeying inland she came upon this resting place that has since become known as a “thin place” and so the common saying in these parts “there is not more than one step between our valley and heaven.”

While sitting in the church before the shrine I began to play hoping that I might cross that divide in time to revisit the archetypal scene of the hunter in pursuit of the hare that was said to have occurred here over thirteen centuries ago. I imagined that morning when Melangell heard in the distance the blister of a hunter’s horn and hounds in mad pursuit of a hare hiding in a thicket. The hare knew that he would soon be discovered and was drawn into the presence of Melangell and hid beneath the folds of her dress. When the hounds encountered God’s presence that encircled her they suddenly retreated. Following closely behind came a wild and angry prince of this world seeking to force his way upon the land. After yelling at his hounds he began gesturing his own might by thrusting his powerful arm into the air shaking his spear over head. She in turn stands firm looking him in the eyes as she quietly rises her slender arms, palms up to the sky. These principalities meet here and waged a war of the spirit that is celebrated and remembered to this day at Pennant Melangell. Their resolve was her promise to pray for him and his kingdom if he would promise to never hunt here again or allow others to do so. As years passed, thousands of men and women, like the hare, have been drawn to this place of peace where the wild animals mingle with the people freely while looking for shelter from adversity.

Performances By

Skellig Michael-A Rock In The Sea: John Doan – harp guitar; Billy Oskay – violin; Blake Applegate, Karl Blume, and Terry Ross – vocals; Cal Scott – keyboards and midi percussion; Jarrod Kaplan – hand percussion: djembe, dumbek, snare drum, cymbels, cow bell, wuhan gong; Randal Bays – celtic guitar.

Wayfarer – On The Path To Holycross Abbey: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott and Billy Oskay – keyboards; Blake Applegate, Karl Blume, John Doan, and Terry Ross – vocals; Jim Chapman – whistle.

Gazing on the Face of the Sea: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott – Keyboards; Jim Chapman – Whistle; Mike Synder – cymbel washes.

The Way of My Fathers: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott – Keyboards; Billy Oskay – viola.

Joseph Arrives in Avalon: John Doan – harp guitar, Nancy Ives – Cello; Mike Synder – cymbel washes.

Run To Sanctuary: John Doan – solo harp guitar.

Festival: John Doan – solo harp guitar; Phil & Gayle Neumann – alto, tenor, and bass crumhorns, frame drum, tambourine, and doodlezock (renaissance bagpipe).

St. Brendan-Recounting the Voyage: John Doan – Porteguese violoa; Jarrod Kaplan – hand percussion: tar, dumbek; Cal Scott – synth Bass; Billy Oskay – violin.

The Hunter and the Hare: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott – keyboards and midi percussion; Randal Bays – celtic guitar.

A Pilgrim’s Hymn: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott – keyboards; Phil & Gayle Neumann – soprano, alto, tenor, and bass recorders; Jim Chapman – Whistle.

Dinas Bran – Procession of the Holy Grail: John Doan – harp guitar; Cal Scott – Keyboards and rainstick; Blake Applegate, Karl Blume, John Doan, and Terry Ross – vocals

Notes

Thanks to Billy Oskay for all the long days of tireless committment in pursuit of an elusive standard of perfection which raised the mark in my playing and gave this project polish; to Jackie and Lauren for sharing billy over the many months of production; to Bob Stark and Scofield his faithful assistant for their masterful mixing; to Cal Scott for providing all the “ear glue” and “ear cookies” with his marvelous sound design work; to all the talented musicians who made me sound better than I really am; Special thanks to Dick and Nell Doan for sharing their love of music and introducing me to the Ink Spots, the Mills Brothers, Fats Domino, Lawrence Welk, among others, and to great songs like Lady of Spain, and Cuando Caliente Del Sol (Love Me With All Your Heart); to my wife Deirdra who shared the wonder of a journey with her warm companionship, and talents as a fine photographer and illustrator; to Stephen Hill, in spite of all he does to administer a record company, oversee artists, graphics, mastering, a national radio program, etc., he still found time to give me important direction and dialogue about this project; to Leyla Hill who makes it possible for Stephen and I to do what we do by doing that so much better than we could if we tried; and to all the people at Hearts of Space for getting behind this project and for spending months of hard work getting it out to the public.

All selections composed by John Doan, Heirloom Serenades (BMI), © p 1999

All selections are produced, arranged, and recorded by Billy Oskay with John Doan at Billy’s Studio February/March 1999.

Mixed by Bob Stark April 1999 at White Horse Studio, Portland, OR.

Sound Design by Billy Oskay and Cal Scott.

Custom modified microphones by Klaus Heyne -German Masterworks.

Custom mastered by Stephen Hill.

Liner notes by John Doan, and edited by Anna Ellendman

Graphic Design by i4 Design, Sausalito

Harp guitar by John Sullivan with Jeffrey Elliott, Portland, Oregon 1986.

On board pickups by Baggs, installation by John Rueter with William Eaton.

John Doan uses GHS Silk & Bronze Medium/light strings

Suggested Reading:

- The Art of Pilgrimage by Phil Cousineau

- The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyun

- Pilgrims by Stephen Platten

- Celt, Druid and Culdee by Isabel Hill Elder

- The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin

- Abbeys, Monasteries and Churches of Great Britain by Frank Bottomly

- Wisdom of the Celtic Saints by Edward Sellner

- Columba by Ian Finlay

- Saint Columba by Adamnan (9th Abbot of Iona)

- Light From the West by William H. Marnell

- Celtioc Heritage by Alwyn Rees and Brinley Rees

- St. Joseph of Arimathea at Glastonbury by Lionel Smithett Lewis

- The Old Irish of New England by Robert Ellis Cahill

- An Age of Saints – Its Relevance For Us Today by Chalwyn James

- Pennant Melangell – Place of Pilgrimage by A. M. Allchin

- Irish Pilgrimage by Daphne Pochin Mould

- Eternal Echoes by John O’Donohue

- Ancient Ireland – From Prehistory to the Middle Ages by Jacquelin O’Brien and Peter Harbison

- Ecclesiatical History of the English People by Father Bebe

- Towards a History of Irish Spirituality by Peter O’Dwyer O Carm

- The Modern Traveller to the Early Irish Church by Lathleen Hughes and Ann Hamlin

- Celtic Christianity by Anthony Duncan

- Irish Shrines & Reliquaries of the Middle Ages by Raghnall O’Floinn

- The Landscape of King Arthur by Geoffrey Ashe

- In Search of the Holy Grail and the Precious Blood by Ean and Deike Begg

- The Grail Quest for the eternal by John Matthews

- The Age of Saints-Its relevance for us Today by Chalwyn James

- The Drama of the Lost Disciples by George Jowett

- The Soul of Celtic Spirituality In the Lives of Its Saints by Michael Mitton

- The Flowering of Ireland – Saints, Scholars & Kings by Katharine Scherman

You must be logged in to view this content.